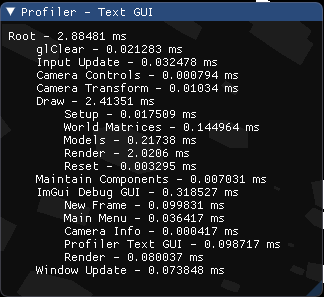

While implementing a profiler for Open Sea, I have realised that I will need a data structure that reflects both the stack-ness of the call stack and the memory of a tree. In other words, a data structure that can be interacted with similarly to a stack — in order to be intuitive to use around functions and blocks of code — but doesn’t lose the data with every pop, so that I can then display that data and use it for optimisation.

Update: My implementation of this idea used in Open Sea is available here. It is for example used in the profiler.

Early in the design process I intended to use a stack to track the blocks of code and their hierarchy, and a separate tree to then write the data into (in this case a label for the block and its duration). While designing the functions that would interact with this pair of structures, I noticed that the actions were mostly mirrored on both. When pushing onto the stack, it would be moving down in the hierarchy of the tree and eventually adding a new leaf. When popping off the stack, it would be finilising the duration calculation and then moving up the hierarchy of the tree. I then decided to merge the two data structures to avoid this duplication and potentionally save some time and memory.

Track

I decided to name the resulting data structure track because it is a tree-stack hybrid, can be used to track the evolution of a stack, and because I have very little imagination for names.

Outwardly, it appears as a stack.

It has the typical push(element), top() and pop() methods.

But the data is stored in a tree and the stack behaviour is replicated by keeping the index of the current node.

The contents of the stack can then be read as the contents of the nodes of the tree along the path from the root to the current node, with the root representing an empty stack and the contents of the current node being on the top of the stack.

In my implementation, the nodes of the tree are stored in a vector and links between them are indices into that vector. From now on, I will be referring to this implementation. The source code is available here.

Implied Root

The root itself is not part of the stored data.

What is stored is actually a forest of subtrees of the implied root.

This is because the root represents the empty stack and therefore should have no contents.

It is present and exactly the same in every track instance, so I decided to omit it from the actual data.

For this end, I assigned the maximum unsigned int value as an indicator of an invalid index.

This value was chosen because there is a negligable chance of the storage vector actually having a node at that index.

A node with invalid parent is considered to be a child of the implied root. In the case of other links (next sibling and first child), invalidity means that there is no such node.

Construction

A new track is constructed by simply constructing an empty storage vector, and setting current and lastChild (used to speed up push) to invalid (i.e. the implied root node and none respectively).

This then represents an empty stack.

Push

if (current != Node::INVALID && store[current].firstChild == Node::INVALID)

store[current].firstChild = tree_size;

if (lastChild != Node::INVALID)

store[lastChild].next = tree_size;

store.emplace_back(current, content);

current = tree_size;

lastChild = Node::INVALID;

tree_size++;

stack_size++;

Pushing onto the stack creates a new node as a child of the current node.

That is where lastChild comes into play.

Because of how the tree is built up, we can easily keep this field set to the index of the last child of the current node.

This allows us to quickly add the index of another child into its next field without having to traverse all children of the current node.

The current index is then set to this new node and lastChild is invalidated, as a newly created node does not have any children.

Complexity

- The first two checks take constant time, because they are equality checks on known fields.

- Next is the new node placement into the vector. This takes amortised constant time.

- After that is just updating four state fields which takes constant time.

Therefore this method takes amortised constant time.

This would be linear time in the number of children of the current node, if lastChild was not used.

Therefore the inclusion of this field improves the performance considerably.

This is largely allowed by the pattern of interaction with the tree (mainly in the pop() method).

Pop

if (current == Node::INVALID)

return;

lastChild = current;

current = store[current].parent;

stack_size--;

Popping off the stack is slightly simpler.

As no data is actually removed, it only involves changes to the current and lastChild fields.

First, the lastChild field is set to the index of the current node as that one is the last child of its parent.

Then current is set to the index of the original node’s parent.

Popping off an empty stack has no effects.

Complexity

- The first check takes constant time, because it is an equality check on a known field.

- The rest is just updating three fields which takes constant time.

Therefore this method takes constant time.

Top

A reference for the top of the stack can be retreived by calling top().

The reference is for the contents of the node, not the whole node, as the stack is formed by the contents of the nodes, not by the nodes themselves.

This can be used to make changes to the top element before popping it off, for example finalising the duration calculation when used in the profiler.

Clear

store.clear();

current = Node::INVALID;

lastChild = Node::INVALID;

stack_size = 0;

tree_size = 0;

Clearing a track returns it into the same state that it was in upon construction.

It cleares the storage vector, resets size counters, and invalidates both current and lastChild.

Complexity

- The clearing of the storage vector takes linear time.

- The rest is just updating four fields which takes constant time.

Therefore this method takes linear time in the number of nodes in the tree.

Indented String Conversion

As a rudimentary means of displaying the full contents of the track, a string conversion is provided.

This consists of a line for each node of the tree (except the implied root, which represents an empty stack).

Each line is indented with TABs based on how many nodes are between it and the root.

The contents of the line are the contents of the node streamed using the << operator.

The resulting string resembles the history of the stack, where time progresses down. Each move to the right is a push, each move to the left is a pop. The exact contents of the stack at each line are: the line, and the contents of the lines above it, going exactly one level of indentation to the left each time until hitting no indentation.

Other Uses

Although I currently only use a track in the Open Sea profiler, there might be other uses. In general, this would be anywhere a stack is used and one would like to know its history. For example debugging of push down automata. These use a stack as an integral part and so knowing the contents of the stack at all times and how they changed throughout the execution might help uncover the cause of some bugs. I would be interested to hear if anyone puts this structure to another use, and what that use is.